A brief history and overview of Kasbah du Toubkal

This article first appeared in the Emirates magazine and is written by Tricia Welsh

As an eager young British adventurer who fell in love with the High Atlas Mountains in Morocco while trekking there in 1972, Mike McHugo had no idea that his life would end up so intrinsically bound to this exotic and mystical country.

Opting out of conventional corporate business, McHugo established Hobo Travel, which eventually grew into the more salubrious, Discover Ltd., operating adventure holidays to Morocco. Today, he is the distant force behind Kasbah du Toubkal, the premier mountain retreat in Morocco.

Kasbah du Toubkal is run through a unique partnership with the local Berber community, with a five per cent levy included in guests’ accommodation bills being funnelled back to the villagers. it is more of a berber hospitality centre than a traditional hotel, where the genuine friendliness, warmth and hospitality are exceptional.

Like many things in life, the Kasbah came to McHugo in a circuitous manner. In 1986, with financial help from family and friends, McHugo bought what is now The Eagle’s Nest in the Cevennes National Park in central southern France, where he lives with his wife and family. He then turned it into a permanent fieldwork base operating educational tours for school and college students. So far, some 20,000 students and teachers from around the world have visited the property.

It was not until 1989 that McHugo, while travelling through Morocco with his brother Chris and their mother, stayed in a small Berber village below a ruined kasbah at the foot of the highest peak in North Africa, the 4167-metre high Mount Toubkal. They were the guests of local mountain guide and respected leader of the local community, Hajj Maurice, with whom Mike had built up a firm friendship over the years.

“We had noticed the crumbling ruin of an old kasbah – originally the summer home of a local feudal chief,” recalls McHugo. “It was Chris who suggested we buy it. He had read that direct foreign investment in Morocco was being encouraged and was apparently going to become easier. It was also seen to be the key to the country’s development.

“After all, he thought, we were possibly as safe a pair of hands as anyone to do something useful and sustainable with the special site.”

On a business level, the two brothers couldn’t be further apart. Chris is very much the “well-heeled consultant formerly with one of the world’s largest agencies” while Mike has been a bus driver, entrepreneur and now educator. What binds them, apart from filial love, is a keenness for North Africa—in particular, Morocco—where they have both trekked extensively through the remote and spectacular mountains.

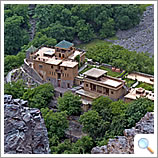

The McHugos, through Discover Ltd. and funds from their French connection, duly bought the property, restored it and, in 1995, opened Kasbah du Toubkal for paying guests. Maurice and his wife, Hajja Arkia, manage the property, employing a team of 32 friendly and efficient staff from nearby villages.

It was not a straightforward project and might easily have gone off the rails had it not been for a fortuitous meeting with pragmatic British architect John Bothamley who, says McHugo, kept the style simple and in the vernacular.

Village labourers used traditional building techniques and local materials in its construction, with everything having to be carried in by hand or on the backs of mules. Power tools could not be used, as electricity didn't arrive in this remote region until 1997.

Perched on imposing outcrop 1,800 metres above sea level, Kasbah du Toubkal crowns Imlil Valley with its population of around 5,000 mostly subsistence farmers, whose own fields and walnut, cherry and apple orchards flourish below.

Its location, high above a waterfall-fed stream where villagers bathe and wash their laundry and opposite a handful of primitive adobe villages that cling to the rocky mountain face beneath the snow-dusted Mount Toubkal, is perfect. Little wonder Hollywood movie director, Martin Scorsese, found it an ideal location for Kundun his film about the Dalai Lama, when it was temporarily converted into a Tibetan monastery.

Today, there are fourteen rooms with ensuite bathrooms, including a three-bedroom family house and separate Berber Salons, which although can be used on a dormitory basis at only 40 euro per night per person, cannot be booked in advance. Plus a conference centre for study groups. The rooms are rustic yet comfortable, with simple berber adornments such as hand-woven carpets, blankets, intricate carved woodwork and oleander branch panelled ceilings.

The project took several years to complete, with each phase being planned as investment funds came to hand and while McHugo learned what the site required in order to address the needs of the clients.

“We already had an established business in the school education market, so the next phase was to make the building more useful for that purpose,” he says. “In 1998, we ran an exclusive trip for YPOs – members of the Young Presidents’ Organisation. We already knew we had an exceptional site, but these participants, who had been almost everywhere and done everything, confirmed it.”

A stay at the kasbah is a unique chance to learn about the Berber culture and simple lifestyles of these proud mountain people who have changed little over the centuries. The village of Imlil comprises some five separate settlement areas with a population of just 1,500. Its location is at the end of the main road system, beyond which narrow footpaths and precipitous mule tracks are the only channels of communications with the outside world.

The Kasbah recently opened a trekking lodge—the first in the area—in a remote location in the heart of the High Atlas Mountains. Built in traditional style, it offers solar-powered underfloor heating and spectacular views a day’s walk away.

To ensure the Kasbah retains its close links with the local community, Discover Ltd. was instrumental in setting up the Imlil Village Association that is funded by the accommodation levy. To date, the association has been able to build a hammam—the region’s first community steam bath—and recently assisted in the construction of a school for 80 children in an outlying valley. It has also instigated a much-needed rubbish disposal system, as well as providing the region’s first ambulance and driver.

Kasbah du Toubkal has won numerous awards for its unique approach to responsible tourism and was mentioned by HRH Prince Charles in an essay he wrote on responsible tourism for Condé Nast Traveller magazine last year. In it, he touched on some ‘excellent examples of good practice, such as the Kasbah du Toubkal’, where restoration was so sympathetic to its original design that ‘visitors regularly believe it to be hundreds of years old’, adding that ‘the approach they followed has since been enforced by His Majesty, the King of Morocco, as a regional standard, ensuring other developments follow’.

The Kasbah has found such wide appeal among its many guests that McHugo keeps them informed through a regular newsletter (to subscribe, use the box in the lefy-hand column).

Today, the Kasbah is a viable business proposition with a positive outcome for all involved. When reflecting on it, McHugo likes to quote the Dalai Lama: “We are good selfish as opposed to bad selfish.”

“I imagine such a project would not be possible without close and deep local ties,” he adds. “I also believe that by our correct behaviour and respect for the local population, hopefully they have come to respect us and also accept some of our differences.”

It is, as a plaque on the Kasbah’s front door reads, a case where ‘Dreams are only the plans of the reasonable’.